Across Africa, the digital economy is expanding at a remarkable speed. Artificial

intelligence, fintech innovations, cloud computing, and mobile-first solutions are

transforming how people live, work, and do business. With this rapid transformation

comes the critical determination of who controls the data that fuels this growth?

The doctrine of data sovereignty has become central to this debate. Policymakers

increasingly regard data not merely as a digital by-product, but as a strategic resource

tied to national security, economic competitiveness, and citizen trust. The sovereignty

debate comes with policy tensions given that while stronger data controls can empower

states to protect privacy, foster local innovation, and build resilient digital ecosystems, a

patchwork of uncoordinated national rules could risk creating digital fragmentation,

raising costs for businesses, discouraging cross-border trade, and deterring investment.

Thus, Africa now stands at a crossroads. Will data sovereignty become a catalyst for

integration and sustainable growth, or a barrier that limits the continent’s ability to

compete in the global digital economy?

In this feature, we examine how Africa can balance localisation, integration, and

investment to build a trusted and competitive digital future.

The term “data sovereignty” has taken on multiple, sometimes conflicting meanings.

Within legal contexts, the notion may refer to a legal entitlement, such as a nation’s right

to regulate its own data or an Indigenous people’s right to govern data about their

communities. As a legal framework, it may also underscore the body of laws determining

which jurisdiction’s rules apply to data storage and access. This includes data localisation

laws that require information to remain within national borders.

Furthermore, the notion has been explained as an extension of national sovereignty in the

sense that control over data is now as fundamental to sovereignty as control over land,

sea, or airspace, linking it to geopolitical power and national security. In reality, these

perspectives are not mutually exclusive. Rather, they reveal that data sovereignty sits at

the intersection of law, capability, and policy ambition.

For African states, a pragmatic understanding is essential. Data sovereignty should be

treated as the lawful and practical ability of a nation or regional bloc to control, govern,

and derive value from data generated within its territory, in a way that protects citizens’

rights, promotes trust, and enables cross-border digital trade.

The conversation on data sovereignty in Africa is unfolding through a patchwork of

national laws, infrastructure investments, and geopolitical alignments that reveal both the

continent’s digital ambitions and its structural constraints. Over 35 African countries have

now enacted some form of data protection legislation, with Nigeria, Kenya, Ghana, and

South Africa among the most advanced.

However, implementation remains inconsistent, with frameworks lacking independent

regulators, clear enforcement mechanisms, or cross-border interoperability provisions. At

the continental level, the African Union Convention on Cyber Security and Personal Data

Protection (the Malabo Convention), adopted in 2014, still faces slow ratification. Fewer

than 20 member states have ratified it, leaving vast regions without harmonised data

protection or cyber governance standards.

This lag contrasts with the European Union’s GDPR and emerging regional initiatives in

Asia, where there are established enforceable norms for data processing, localisation, and

privacy. Africa’s lag in achieving similar coherence underscores a deeper policy dilemma

as to how to assert digital sovereignty without stifling the innovation and integration

needed for scale.

A key trend is the push for data localisation, requiring companies to store or process data

within national borders as a means of asserting control. This approach is influenced by

governance models like China’s state-centric model that asserts the government's

ultimate authority over data within its borders, driven by national security, economic

development, and social stability goal. Senegal was the first African country to adopt the

approach of emphasising strong state control and mandatory local hosting.

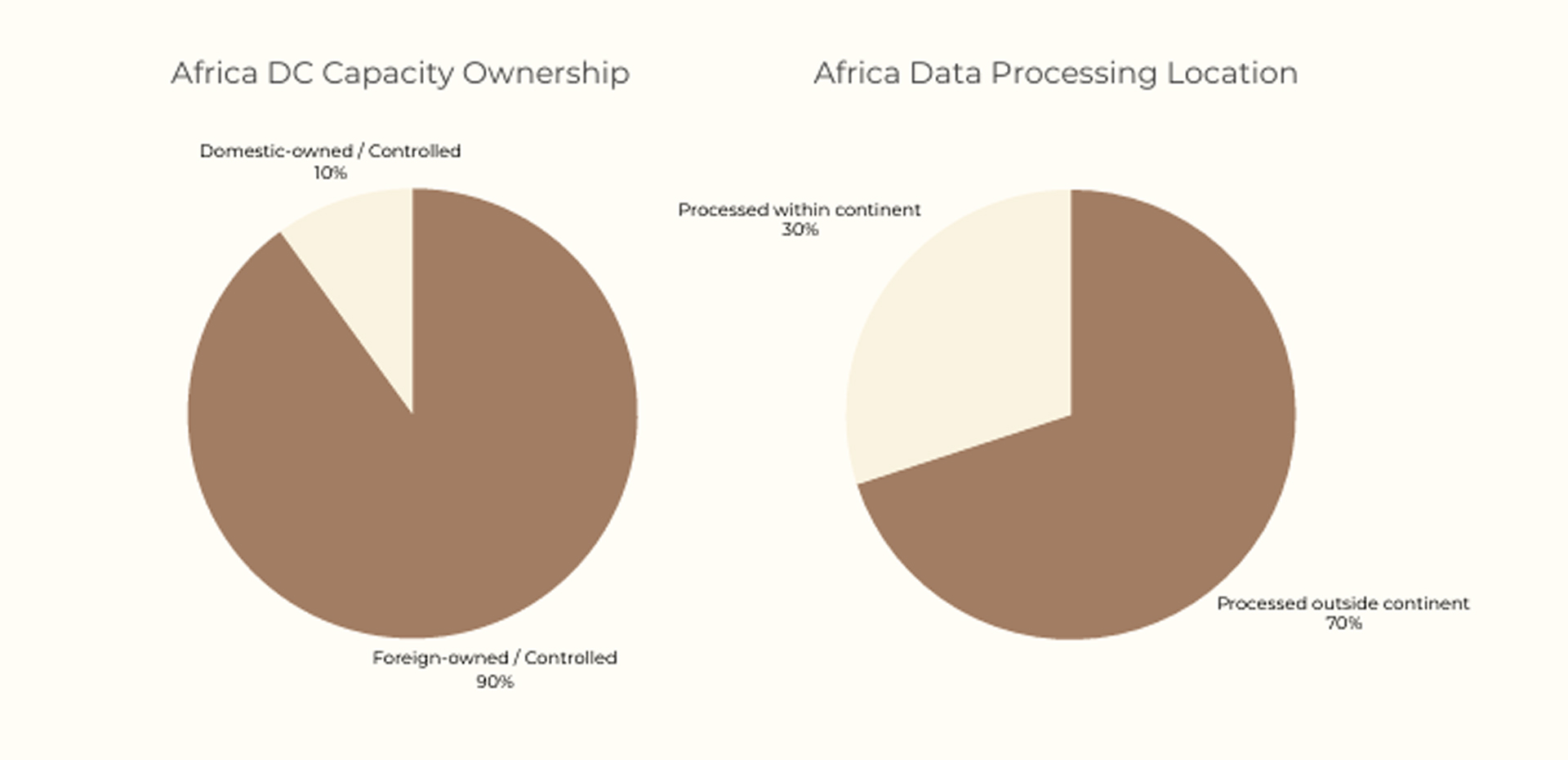

Across the African continent, over 700 new data centres are projected to be built within

the next decade, many of which are to be funded or operated by foreign hyperscalers and

multinational corporations. While this reflects strong investor confidence, it also raises

concerns about “data capitalism” or even “data colonialism”, where foreign entities

dominate digital infrastructure ownership, value extraction, and governance. Without

sufficient local energy reliability, connectivity, skills and a balanced regulatory framework,

these facilities risk becoming enclaves of external control rather than engines of local

digital empowerment.

What is clear is that true capacity and digital equality are crucial in balancing the policy

reasons for data regulation in this area since Africa’s pursuit of data sovereignty is purely a

geopolitical balancing act that must reconcile legitimate security and economic interests

with the risk of new forms of dependency.

While the appeal of data sovereignty is clear - promising national control, economic empowerment, and digital trust, its practical implementation presents significant challenges. Understanding them is crucial for African governments and businesses seeking to build sustainable digital economies. These challenges are presented across the key focus areas outlined below.

Unlike land, oil, or gold, data is non-rivalrous, which means it can be copied, shared,

and transferred at near-zero cost without any loss of quality. This fluidity makes

traditional sovereignty analogies (such as territory, borders, ownership) difficult to

sustain. Further, the meaning and value of data are context-dependent and can

alternate across applications, sectors, and geographies. In Africa’s emerging data

markets, this means sovereignty cannot simply mean “keeping data at home.”

Instead, it must mean developing the capacity to understand, govern, and extract

value from data, wherever it flows.

Digital sovereignty must extend beyond data localization. While there is justification

for the approach of mandating data to be stored within national borders or in locally

owned data centres, there may simply risk creating isolated data silos which barely

yield real autonomy or value creation without adequate governance frameworks,

technical capacity, or regulatory oversight.

Recommendation: True sovereignty must therefore be functional, not merely

territorial and will require the capability to understand, govern, and monetise data

flows, wherever they occur. This means investing in the analytical, institutional, and

technological capacity to extract insight, ensure compliance, and participate

competitively in global digital value chains. Regional approaches under frameworks

like the AU Data Policy Framework or the AfCFTA Digital Trade Protocol can also help

reframe sovereignty as shared capability rather than rigid localisation, promoting

both control and connectivity.

Africa’s data infrastructure remains heavily reliant on foreign hyperscalers and external cloud ecosystems, which control where data is stored, how it is managed, and who can access it. Centraliszed cloud infrastructure, combined with inadequate local connectivity and energy reliability, creates a position of digital dependency.

Recommendation: African governments must pursue technical sovereignty and the capacity to design, manage, and interconnect their own digital infrastructure. This means promoting interoperable, modular, and open architectures that prevent vendor lock-in, expanding regional cloud infrastructure partnerships, and incentivising African-owned data infrastructure through blended financing and public–private models.

Sovereignty is meaningless without comprehension. Across the continent, both

public institutions and private enterprises increasingly adopt digital platforms and

cloud services without a clear grasp of where their data resides, under what legal

regimes it operates, or how it is processed and monetised. This epistemic gap

creates vulnerabilities to data misuse, privacy breaches, and external control. It also

constrains innovation, as uncertainty about compliance deters firms, especially

SMEs, from embracing cloud technologies or cross-border services. Bridging this

gap demands a multi-level response.

Recommendation: Governments must strengthen regulatory literacy and

institutional capability. Attention should also be placed on establishing independent

data authorities empowered to audit, trace, and assess data flows. Businesses need

governance frameworks and risk-assessment tools that map their data assets and

obligations. Regionally, shared standards for data classification, metadata

transparency, and legal interoperability could enable Africa to manage its data

ecosystems with greater confidence.

Parsons stands at the forefront of Africa’s evolving data landscape, serving as the go-to

Firm for organisations and even the government on navigating the complex intersection

of data governance, regulatory compliance and digital sovereignty. We understand that

Africa’s digital transformation depends not only on technological innovation, but also on

the creation of robust, context-sensitive frameworks that protect data, foster trust and

promote sustainable digital growth.

Leveraging our multidisciplinary expertise, Parsons provides end-to-end advisory support

on data governance, privacy compliance, cross-border data flows, localisation strategies,

and policy development.

Africa’s data sovereignty challenge is not just about where data is stored but who owns,

governs, and benefits from it. True digital sovereignty will require African-owned

infrastructure, indigenous data governance frameworks, and capacity-building initiatives

that empower local regulators, businesses, and civil society to manage data responsibly

and transparently.

Momentum is building for more coherent continental action. The African Continental Free

Trade Area (AfCFTA) Digital Trade Protocol and the AU Data Policy Framework represent

important steps toward regional harmonisation, interoperability, and cross-border trust. If

effectively implemented, these initiatives could position Africa not as a passive consumer

of global data norms but as an active architect of its digital destiny.

Legal Disclaimer: This publication is intended for general informational purposes only

and is not a substitute for professional legal advice. The information provided herein may

not be applicable to your specific circumstances and should not be relied upon as legal

counsel. For advice tailored to your situation, you should consult with qualified legal

counsel.

Contact us to discuss opportunities across Africa’s critical digital economy at

info@Parsons-legal.com.

1. African Development Bank Group, ‘Congo: New Data Centre Funded by African

Development Bank Will Cement National and Subregional Digital Sovereignty’ (News

and Events, 17 May 2024) https://www.afdb.org/en/news-and-events/congo-new-data

centre funded-african-development-bank-will-cement-national-and-subregional

digital sovereignty-70847

2. Coleman D, ‘Digital Colonialism: The 21st Century Scramble for Africa through the

Extraction and Control of User Data and the Limitations of Data Protection Laws’

(2019)

24(2)

Michigan

Journal

https://doi.org/10.36643/mjrl.24.2.digital

3. Soulé F, Navigating Africa’s Digital Partnerships in a Context of Global Rivalry (CIGI

Policy Brief No 180, 2023) https://www.cigionline.org/publications/navigating-africas

digital-partnerships-in a-context-of-global-rivalry/

4. African Union Commission, African Union Data Policy Framework (Addis Ababa, 2022)

https://au.int/en/documents/20220329/african-union-data-policy-framework

5. Economic Commission for Africa, Building Africa’s Data Ecosystem for Sustainable

Development (UNECA, 2023) https://repository.uneca.org/

6. Kwet M, ‘Digital Colonialism: US Empire and the New Imperialism in the Global South’

(2019) 6(2) Race & Class 62

7. Makulilo AB, ‘Data Protection in Africa: An Overview of Legal and Institutional

Frameworks’ (2021) International Data Privacy Law 11(4) 331

8. Ndung’u N, Signé L and Stork C, The Future of Africa’s Digital Economy: Paving the

Road to Inclusive Growth (https://www.brookings.edu/ Institution, 2022)

9. Nyst C and Monaco N, Government Access to User Data: A Comparative Analysis of

Surveillance Laws and Practices in Africa (Global Network Initiative, 2021)

https://globalnetworkinitiative.org/

10. Taylor L and Broeders D, ‘In the Name of Development: Power, Profit and the

Datafication of the Global South’ (2022) 40(3) Geoforum 153

11. World Bank, Digital Africa: Technological Transformation for Jobs (World Bank, 2023)

https://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/digital-africa